- iosphere

- Posts

- #7: The Judge Judy Rule

#7: The Judge Judy Rule

My modest contribution to the field of journalistic ethics.

NOTE: I wanted to write about political violence this week, in the wake of Charlie Kirk’s death, but I’m too tired and sad and crushed by the enormity of the subject. Therefore I am just running the essay I originally had in the pipe. Perhaps another time.

Accuracy. Fairness. Non-partisanship. The right of reply. These are among the foundational principles of my probably doomed vocation.

Personally, though, there is one other little rule that helps me stay sane when all around me is on fire. I call it the Judge Judy Rule, and it's very simple: "Don't piss on my leg and tell me it's raining."

But first: the headlines.

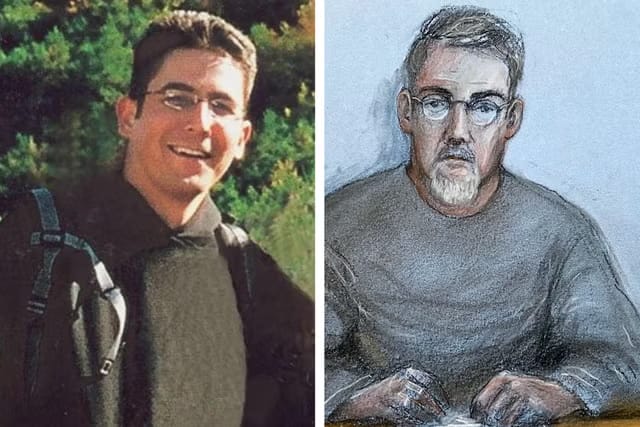

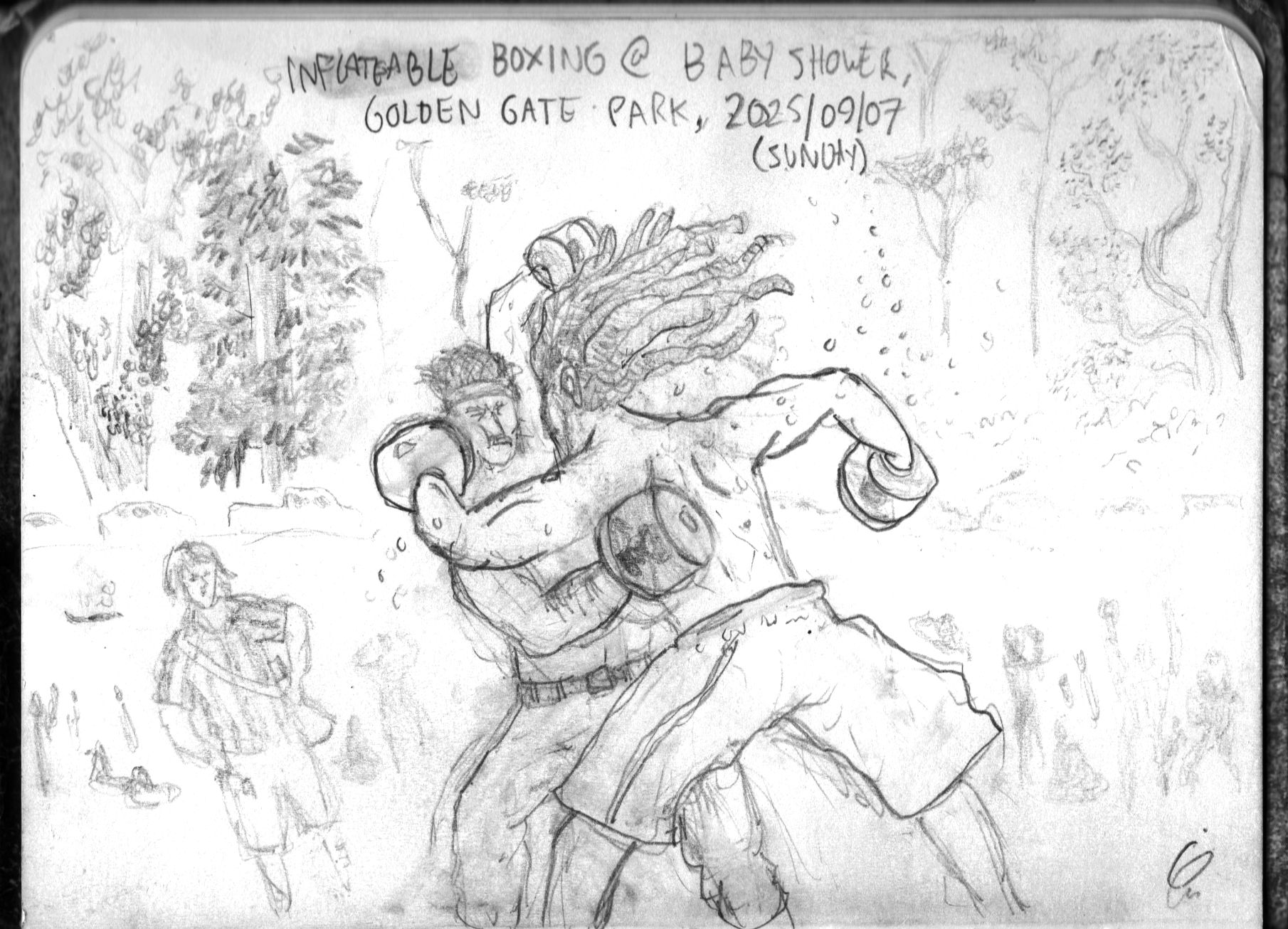

Just an incredibly Bay Area story. A tattooed animal rights activist and Linux programmer (!) allegedly bombs a biotech firm (no deaths or injuries), then vanishes into the San Francisco fog. Now he’s fighting extradition from the UK, arguing he won’t get a fair trial under Trump. Also, his last name is literally ‘San Diego’. |

‘Fierce meteorological debate’

So anyway. Like a chump, I actually believe in all that shit that journalists say to dignify and justify our industry. I truly take those principles very seriously.

The problem is that powerful people and institutions don’t. They know all about our vaunted ethics, but have no issue exploiting them to make us accessories to their agendas.

PRs and corporate lawyers lean on us not to report credible allegations because they aren’t yet proven. Politicians attack us or try to defund us on the pretext that we're 'biased'. Conspiracy theorists, ideological partisans, and disinformation merchants — often all the same thing, these days — try to mob us into lending credence to their twisted fantasies.

The pressure towards false balance, false equivalence, and false uncertainty is heavy and relentless. And if that pressure overpowers us, we may end up betraying our principles under the guise of following them.

To prevent this, we need spines as well as principles. That our ethics should be focused on uncomfortable truths is hardly a new idea; oft-quoted maxims like "speak truth to power" or "comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable" have similar aims.

Maybe you've heard that aphorism about how if one person says it's raining, while another says it's not, the job of a journalist is to go outside and check, not to credulously report both sides. It's often used in reference to the false debate about whether global warming is happening (it is), or in discussions of how journalists should deal with Donald Trump's unbreakable commitment to the ignoble art of bullshit.

The Judge Judy Rule is a corollary of that. If you check outside and find that the rain is really a stream of pee from some weirdo on your rooftop, you can and should just say that. "MAN TINKLES ON JUDGE THEN CLAIMS IT WAS RAIN" is a better headline, both ethically and commercially, than "Urination in Courthouse Sparks Fierce Meteorological Debate”.

This doesn’t mean we can neglect our other principles. Obviously we should give those named in our stories a right of reply. We should uphold the presumption of innocence when reporting on allegations of criminality. We should be clear about our source for each claim, honest about the degree of uncertainty, and always conscious that we could be wrong. And, of course, sometimes we just have to do what our lawyers tell us to.

But we serve nobody when we insist on upholding an artificial uncertainty. If the probability tilts unmistakably one way, we shouldn't hide that from our readers. Nor should we feel any professional obligation to reframe our reporting around opposing contestations that we know to be implausible, misleading, or just plain dishonest.

Let's take a moment to put this in more technical terms. As you've probably noticed, there is a spectrum of linguistic quirks journalists deploy at different levels of certainty:

At high certainty, we simply assert things as fact. "The Galactic Empire annihilated the entire world of Alderaan on Thursday night, along with roughly 2bn people who lived there — an undeniable act of genocide in revenge for the planet’s alleged rebel ties.”

At medium certainty — which I'd say actually covers more than 50% of the chart — we use distancing language such as "claimed" "alleged" or "reportedly", while often still framing our articles around said allegations. "The Galactic Empire destroyed Alderaan and its 2bn inhabitants using a previously secret super-weapon, neutral observers and rebel diplomats have alleged."

A healthy respect for the rule of law (and, in the UK, contempt of court laws) compels us to put almost all criminal allegations in this zone by default, which is why I get annoyed when people on social media bitch about "alleged" in news reports. Like yeah dog, laws are a thing!

Low certainty is where we start bending entire articles around the idea of "debates" and "disputes", where each side is treated as equally plausible or legitimate in substance rather than as a formality of due process. "As mystery deepens over who or what caused the destruction of Alderaan and its 2bn inhabitants, both sides of the Galactic Civil War have sought to blame the other."

(To be clear, certainty is far from the only factor that influences this choice of framings.)

Putting that Judge Judy Rule into less polemical (or urinary) language, we could say: 1) Contrary to what some newsfolk apparently believe, low-certainly framings have big downsides and are not a risk-free fallback — especially when one side is lying to you. 2) It is often just as unethical to use low-certainty framing for a higher-certainty story as it is to do the opposite.

There is, I'll admit, a fine line between "calling things what they are" and "asserting your own preconceptions as fact". In fast-moving situations, inside a blizzard of shifting claims and counter-claims from highly motivated parties, where is the border between Judge Judy and Judge Dredd?

No rulebook can ever answer this question for every possible situation. Theory only tells you how to decide, not what to decide. All we can do is use our judgement, in the moment and based on the circumstances, and write what we believe we can honestly justify when we're called before our gods.

We'll never get it right 100% of the time. But at least we can make it harder for the bastards to piss on everyone's legs.